In 1968, rage over the United States’ treatment of Black America was boiling over. It culminated that year in a protest at the Summer Olympics in Mexico City that shocked the world. But perhaps the lid blowing off the kettle shouldn’t have been so surprising.

In May of 1967, Martin Luther King Jr. admitted that his “dream” of 1963 had “turned into a nightmare.” The uprisings later that summer reflected long-festering racial inequality. And as 1968 dawned, poverty was rampant in Black America.

In Memphis, striking sanitation workers made about a dollar an hour. The Kerner Report, which was released in March of 1968, sounded ominous:

“What white Americans have never fully understood — but what the Negro can never forget — is that white society is deeply implicated in the ghetto. White institutions created it, white institutions maintain it, and white society condones it.”

Less than one month later, King was shot down in Memphis supporting those very sanitation workers.

1968 also saw continued protests over the Vietnam War, the assassination of Robert Kennedy, and the live broadcast across the nation of the Chicago Police beating demonstrators at the Democratic National Convention. As the 1968 Olympics Games began, track athletes John Carlos and Tommie Smith made a decision. Something had to be said to the world about the promise of America going up in smoke.

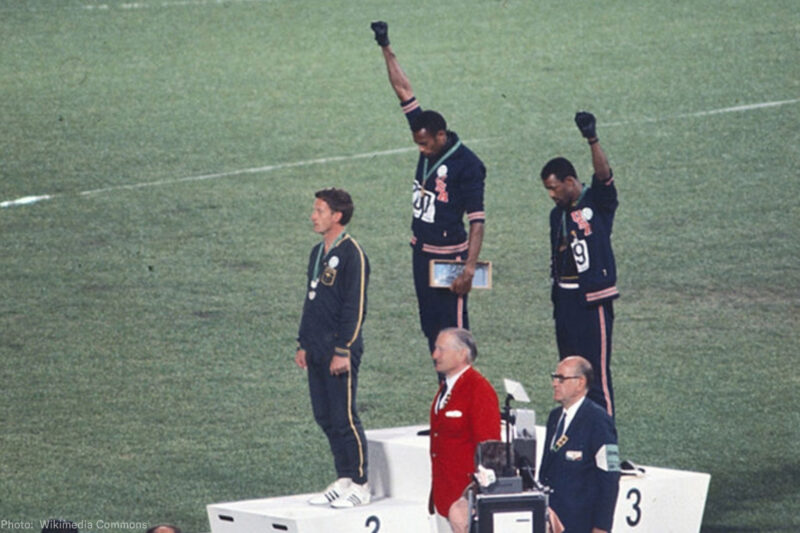

Smith and Carlos won the gold and bronze medals respectively in the 200-meter event. What came next shocked the world. As Smith and Carlos walked to the podium, they took off their shoes to protest poverty. They wore beads and a scarf to protest lynchings — the last lynching of the 20th century had not yet occurred in 1968. Carlos unzipped his Olympic jacket, in defiance of Olympic etiquette, but in support of “all the working-class people — black and white — in Harlem who had to struggle and work with their hands all day.”

Carlos also deliberately covered up the “USA” on his uniform with a black t-shirt to “reflect the shame I felt that my country was traveling at a snail’s pace toward something that should be obvious to all people of good will.” And when the national anthem was played, Smith and Carlos lowered their heads and raised their fists. They only had one pair of gloves so Smith put a black glove on his raised right fist; Carlos covered his left fist. The world was watching.

Smith and Carlos were protesting Black poverty that existed in a sea of prosperity. They were protesting police violence against Blacks and other people of color who spoke up about America’s shortcomings. Yet just as we fail to see the connection between King and young Black activists today, we are blind to the parallels between Smith and Carlos on the one hand and Colin Kaepernick and other modern day protesting athletes on the other. The protests are mirror images of each other and, sadly, the issues are the same.

Last year, Clemson University’s football coach Dabo Swinney claimed King would not have supported kneeling during the anthem. Has he forgotten the marches? The sit-ins? The fact that King was arrested more than 30 times in 12 years? King was always ready to inconvenience himself and America in order to move us toward justice. The idea of privileged athletes kneeling quietly and respectfully during the anthem to make America look at its failings would have made King proud.

Like Carlos and Smith before him, Kaepernick and other present-day athletes are protesting silently but publically. They make no attempt to disrupt the singing of the anthem or to interfere with the way anyone else wants to behave. And, like Smith and Carlos, Kaepernick and his fellow protesting athletes have said time and time again what they are protesting — racism and police violence in Black and Brown communities.

This should surprise nobody. The issues are identical to the ones that concerned Smith and Carlos 50 years ago.

Despite being instantly reviled for their protest, Carlos and Smith are in good company. Muhammed Ali refused to step forward in his draft line; he lost his title and was convicted of a crime. Today we honor him as an American hero. Jackie Robinson — who was placed in a segregated military unit during World War II — refused to stand up when he was ordered to the back of the bus, taking a court martial instead. Today he is an icon of the civil rights movements.

Likewise, Smith and Carlos watched as their athletic careers were sabotaged. They were blacklisted as anti-American. They received death threats. But almost 50 years later, a statue of their protest was installed at the Smithsonian Institution’s new National Museum of African American History and Culture. San Jose State University has even awarded them honorary doctorates.

It took 50 years too long to recognize the righteousness of Carlos and Smith’s actions. Today’s protesting athletes deserve better — but I have a feeling they don’t mind playing the villain if it gets America to address the urgent issues they continue to raise. And that, right there, is heroism.