It is no accident that much of the United States remains segregated. Decades of slavery, Jim Crow laws, discriminatory lending practices, and intentional policy choices at the federal, state, and local level — most of which were enacted within the last 80 years — helped make it so.

The Fair Housing Act, passed in 1968, just a week after Martin Luther King, Jr. was assassinated, was meant to address the decades of discrimination that led to such segregation. The FHA made it illegal to discriminate against anyone buying or renting a house because of their race, color, religion, sex, or national origin (it’s since been amended to include family status and disability, too). But it also sought to replace segregation in America with “truly integrated and balanced living patterns” by requiring agencies to “affirmatively” further fair housing in all programs related to housing.

The FHA brought about a sea change with respect to individual housing discrimination — Americans today would be shocked to find an apartment listing that indicated Black people or women with children could not apply. But its promise of integrating neighborhoods has been left largely unfulfilled. As former Vice President Walter Mondale, who co-authored the legislation, pointed out recently in a New York Times op-ed, the FHA is the “most ignored” of the era’s civil rights laws.

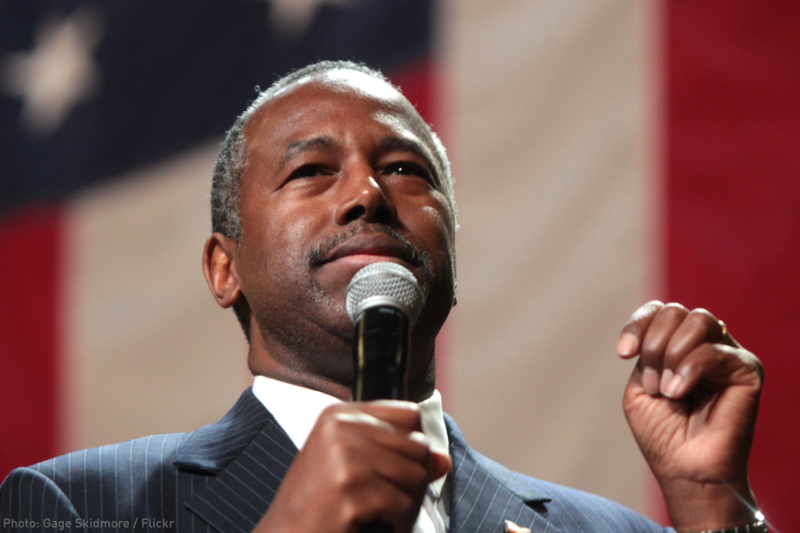

It seems like Secretary Ben Carson, head of the Department of Housing and Urban Development, would like to keep it that way. In January, the agency suspended the only regulation to ever give the FHA real leverage in ending segregation. The move puts housing integration in serious jeopardy, so we’re challenging it in court.

Since it was enacted, successive presidential administrations largely ignored their affirmative obligations to create fair housing, allowing federal government dollars to flow uninterrupted to cities and towns that have policies in place that maintain segregation. Then, in 2015, the Obama administration finally began to seriously address this issue by putting in place a regulation called the Affirmatively Further Fair Housing (AFFH) Rule. The rule required cities and towns to create a plan to address segregation and discrimination and to lay out concrete goals for bringing fair housing and opportunity to members of all the groups protected by the FHA before receiving government money. Examples of these goals include building affordable housing in areas well-served by transit and prohibiting landlords from discriminating against people who use a government subsidy to pay part of their rent.

In the first few years it was in effect, it became clear that the AFFH process gave grantees an important new tool to attack the old problem of segregation. AFFH also proved valuable in addressing fair housing issues that were previously unnoticed. For example, the city of Ithaca, New York, used the AFFH process to prioritize addressing policies and practices that displace victims of domestic violence, sexual assault, and stalking.

But in January, HUD announced that it would not require grantees to engage in the AFFH process until 2020 at the earliest (and, because of the way the process is timed, not until 2024 in most cases). This suspension means that HUD will continue to give out money without doing anything to check whether grantees are using it in ways that perpetuate segregation and undermine fair housing.

During his presidential campaign, Secretary Carson analogized the AFFH Rule to a “failed socialist experiment” and dismissed it as a government attempt to “legislate racial equality.” But the AFFH Rule is nothing of the sort: In fact, it gives local governments wide latitude to create locally appropriate solutions to housing issues that affect not only people of color, but also families with children, people with disabilities, and victims of crime, among others.

Not only is it unacceptable to delay the fulfillment of the FHA’s promise any longer — it’s also illegal. If HUD wanted to suspend the AFFH Rule, the law requires that it provide the public with notice and an opportunity to weigh in. And HUD would have to replace the AFFH Rule with something else that fulfills its statutory duty to affirmatively further fair housing. That’s why we filed suit today on behalf of the National Fair Housing Alliance, Texas Low Income Housing Information Service, and Texas Appleseed, three leading fair housing organizations whose work has been severely undermined by the suspension. Joining us as co-counsel are the law firm of Relman, Dane & Colfax; the Lawyers’ Committee for Civil Rights Under Law; the NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund; the Poverty & Race Research Action Council; and Public Citizen Litigation Group.

All the AFFH Rule requires is that communities seeking federal housing dollars take steps to counteract the history of government-sponsored segregation and to promote equal housing opportunities for all. As the Fair Housing Act turns 50 amid a persistently and illegally divided America, it’s the least we can do.