In the United States, the freedom struggle of Black people and the struggle for prisoners' rights have long been intertwined. After the abolition of slavery, incarceration combined with forced labor was used as a means of continued control of the newly freed Black population in the southern states, re-creating the brutal exploitation that had purportedly been abolished by the 13th Amendment. Prisoners were leased out to work for private employers; conditions were horrific and death rates shockingly high. Sometimes characterized as "worse than slavery," the convict lease system persisted into the 20th century, and ending it was a priority for the NAACP and other civil rights organizations.

In September 1971, at Attica Correctional Facility in New York, hundreds of prisoners rebelled and occupied the prison, demanding an end to abusive and inhumane conditions. Although Black, Latino, and white prisoners participated in the uprising, it was sparked in part by rampant racial discrimination and race-based abuse of Black prisoners. The Attica rebellion was crushed by police, killing 39 people, but the modern prisoners' rights movement was born, and the following year, the ACLU established the National Prison Project to lead its work in this area.

Much has been accomplished in the intervening 40 years. Overt racial segregation in prisons and jails, once routine, has now largely been eradicated. But no victory ever stays won. In 1995, Garrison Johnson, a Black prisoner in California, sued to challenge a policy of racial segregation in the state's prisons. When the case reached the Supreme Court, the state actually defended its policy, arguing that it had to maintain racial segregation as a security measure, and that the Court should defer to its decision to do so. Fortunately the Court rejected this invitation to return to the bad old days of Jim Crow, and ruled that classifying prisoners by race is permissible only if the state can show that doing so is "narrowly tailored to serve a compelling state interest" – a showing no state has been able to make.

Today a major focus of the National Prison Project's work is reversing the misguided policies that have given the United States the largest prison population in the world, both per capita and in absolute numbers. We continue to fight for safe, humane, and decent conditions for the 2.3 million people behind bars. And we are challenging new forms of discrimination, like the Alabama policy that segregates prisoners living with HIV, requires them to wear armbands advertising their HIV status, and bars them from prison jobs, work release, and other important rehabilitative programs.

As we celebrate Black History Month 2012, there is cause for optimism and hope. After nearly 40 years of relentless growth, the U.S. prison population actually declined last year. And while the burden of mass incarceration still falls with crushing disproportionality on Black people, their rate of incarceration has decreased for the last two years.

Martin Luther King Jr. taught us that "the moral arc of the universe is long, but it bends toward justice." That's true in the struggle for civil rights, and equally true in the struggle for prisoners' rights.

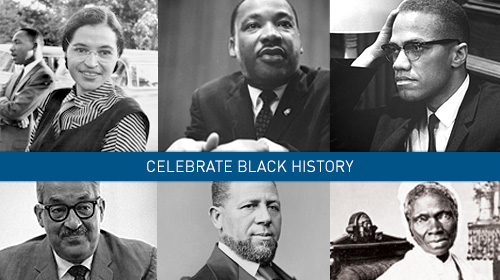

Do you know who’s pictured in our Celebrate Black History logo? Top row, from left to right: Rosa Parks, Martin Luther King, Jr. and Malcolm X. Bottom row, from left to right: Thurgood Marshall, Hiram Rhodes Revels and Sojourner Truth.

Learn more about racial justice: Sign up for breaking news alerts, follow us on Twitter, and like us on Facebook.

Stay informed

Sign up to be the first to hear about how to take action.

By completing this form, I agree to receive occasional emails per the terms of the ACLU's privacy statement.

By completing this form, I agree to receive occasional emails per the terms of the ACLU's privacy statement.