Decarceration and Crime During COVID-19

COVID-19 presents an enormous risk to those in carceral facilities and their surrounding communities. Since the pandemic began, more than 50,000 people in prison have tested positive for the coronavirus, and over 600 have died. These infections and deaths were largely preventable, as we demonstrated in April by working with academic partners to build an epidemiological model that illustrated the deadly threat of COVID-19 in jails. In response to this crisis — and in many localities, only after substantial public pressure and threats of litigation — some governors, sheriffs, and judges made the decision to shift detention policies to prioritize protecting the lives of those who live and work in jails and prisons. Some states and localities reduced low-level arrests, or set bail to $0 for certain charges. Others released a small subset of incarcerated people who were nearing the end of their term or were most vulnerable to the disease — sometimes under court order.

While no jail system has gone far enough, county jails and state prison systems across the U.S. have taken differing levels of action, allowing for a unique opportunity to explore the relationship between decarceration and crime in the community. To explore this, the ACLU’s Analytics team looked for data on jail population and crime in locations with the largest jail and overall populations. We were able to find reported data on both from 29 localities. (Crime data more recent than May was not readily available during analysis.)

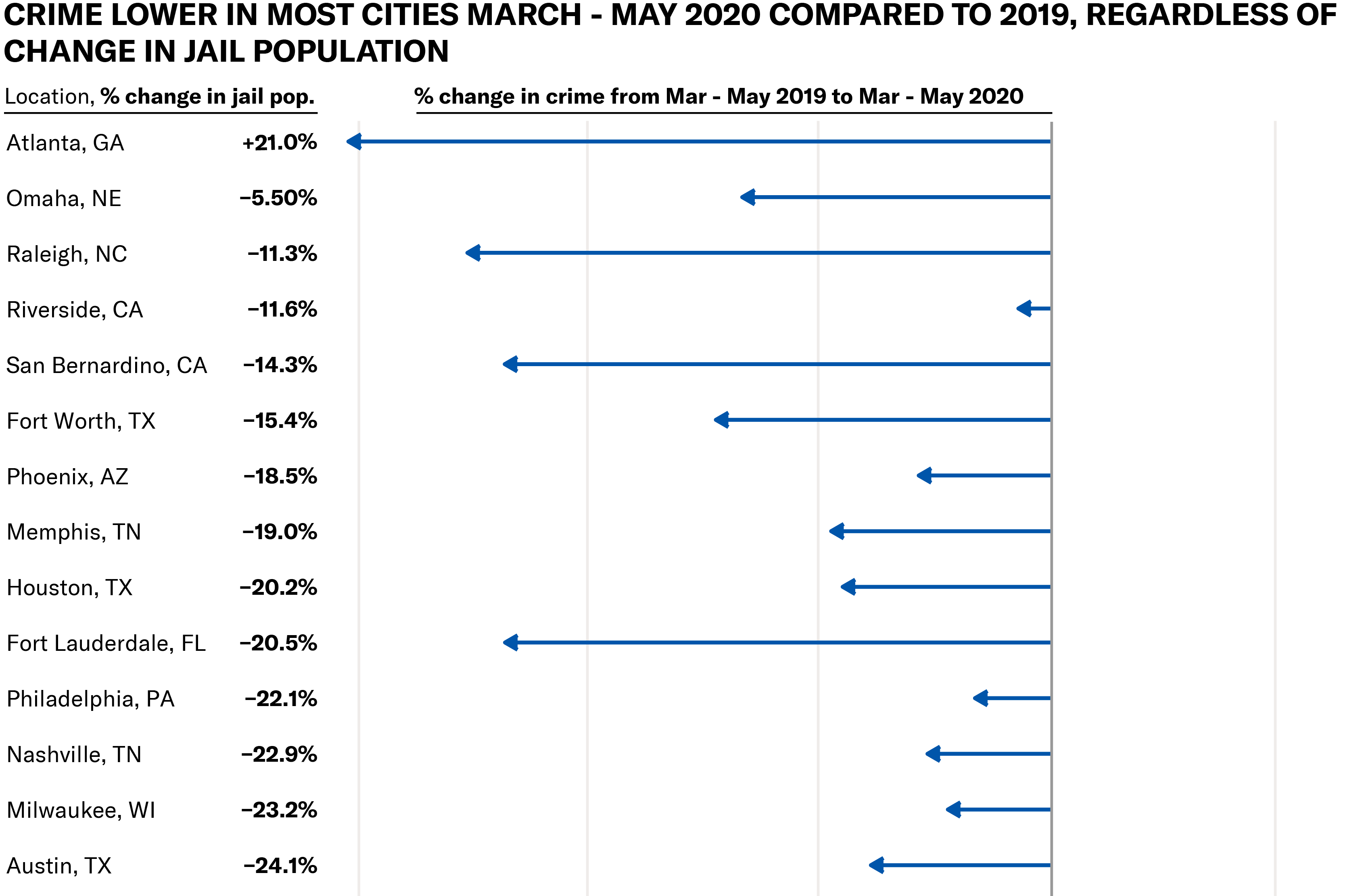

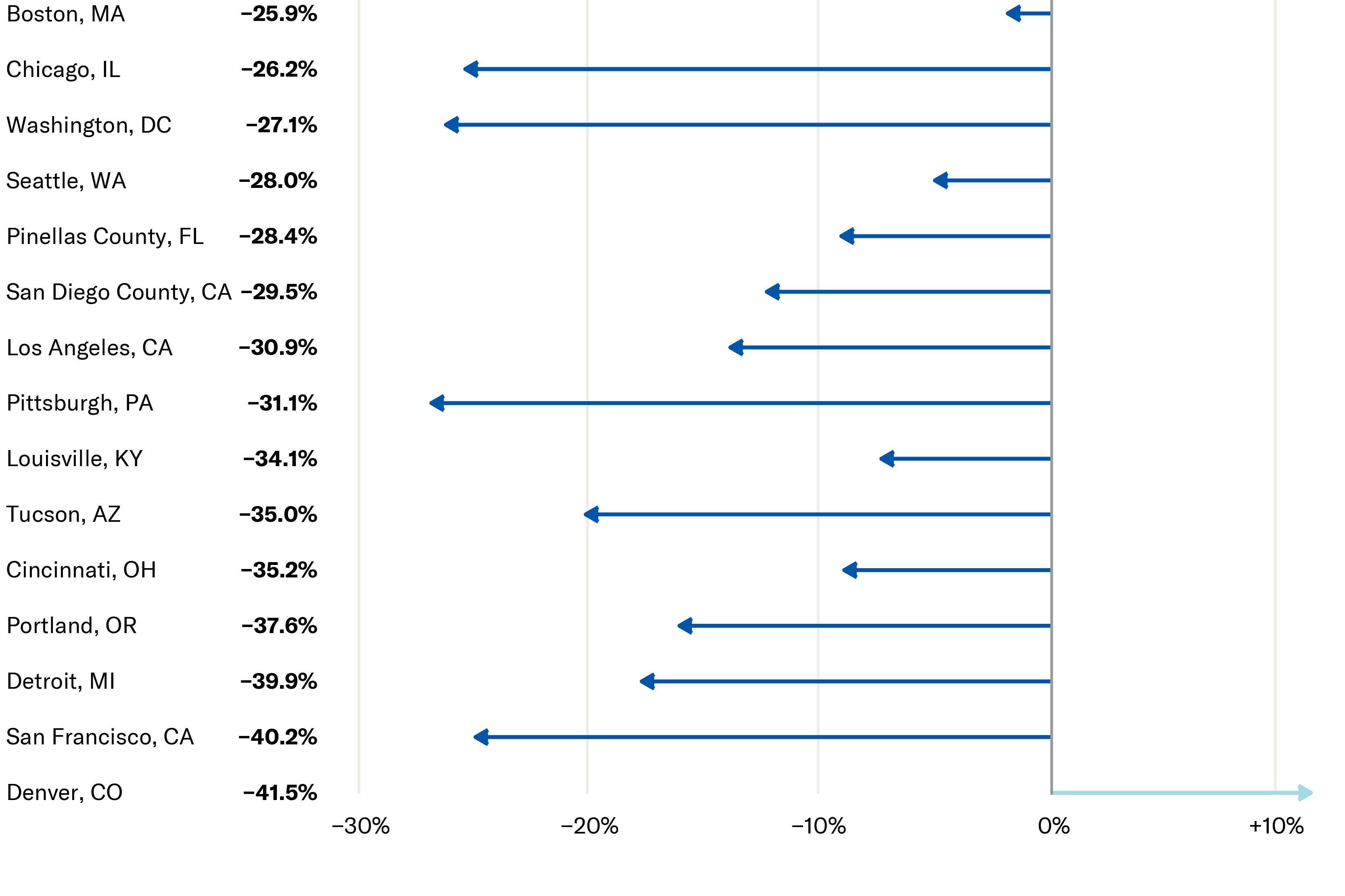

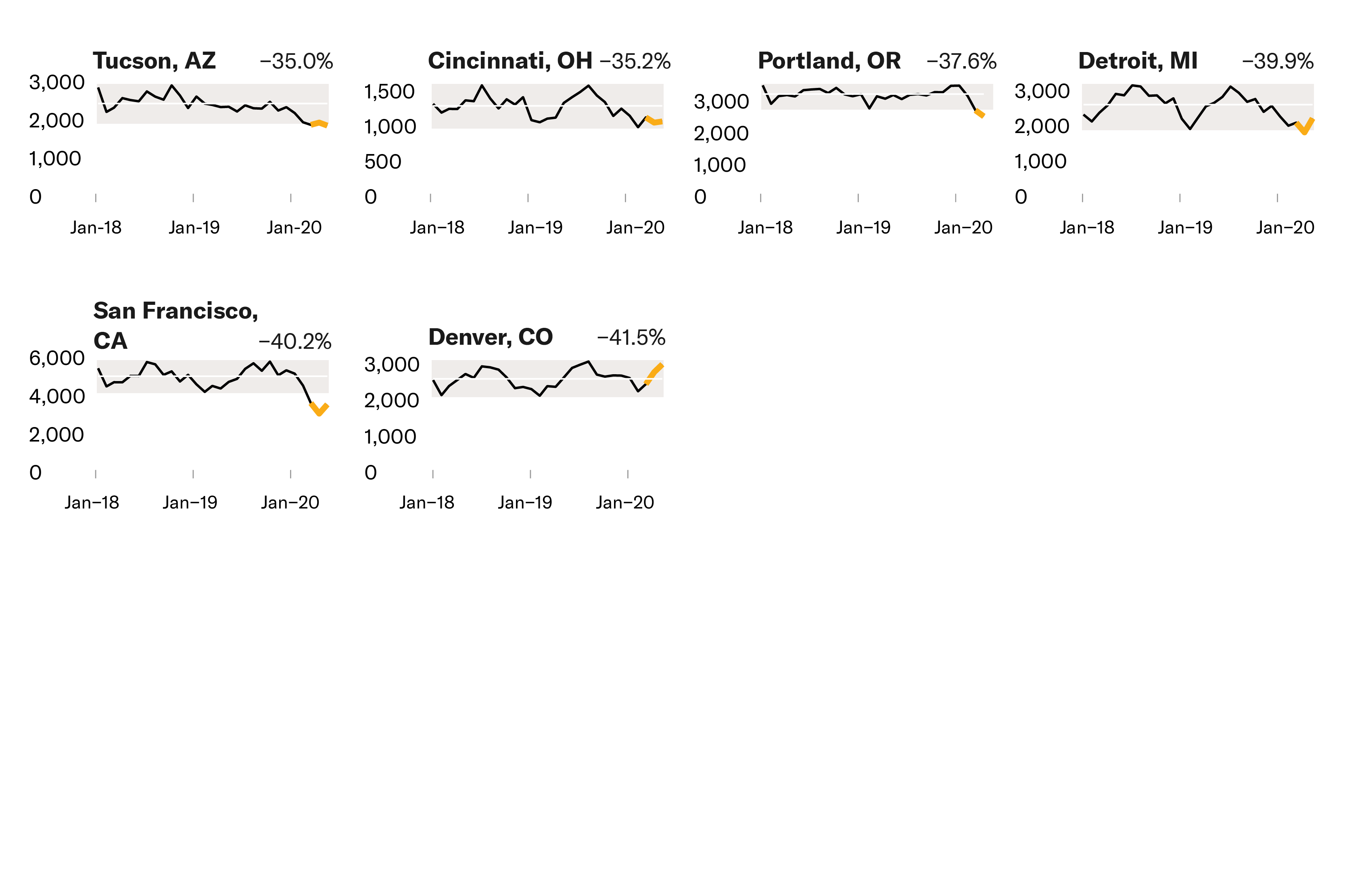

Nearly every county jail that we examined reduced their population, if only slightly, between the end of February and the end of April. Over this time period, we found that the reduction in jail population was functionally unrelated to crime trends in the following months. In fact, in nearly every city explored, fewer crimes occurred between March and May in 2020 compared to the same time period in 2019, regardless of the magnitude of the difference in jail population.

Note: Police data is often dynamic, and constantly updated based on new reports. Reported incidents may have changed since time of analysis (early July, 2020).

Note: Police data is often dynamic, and constantly updated based on new reports. Reported incidents may have changed since time of analysis (early July, 2020).

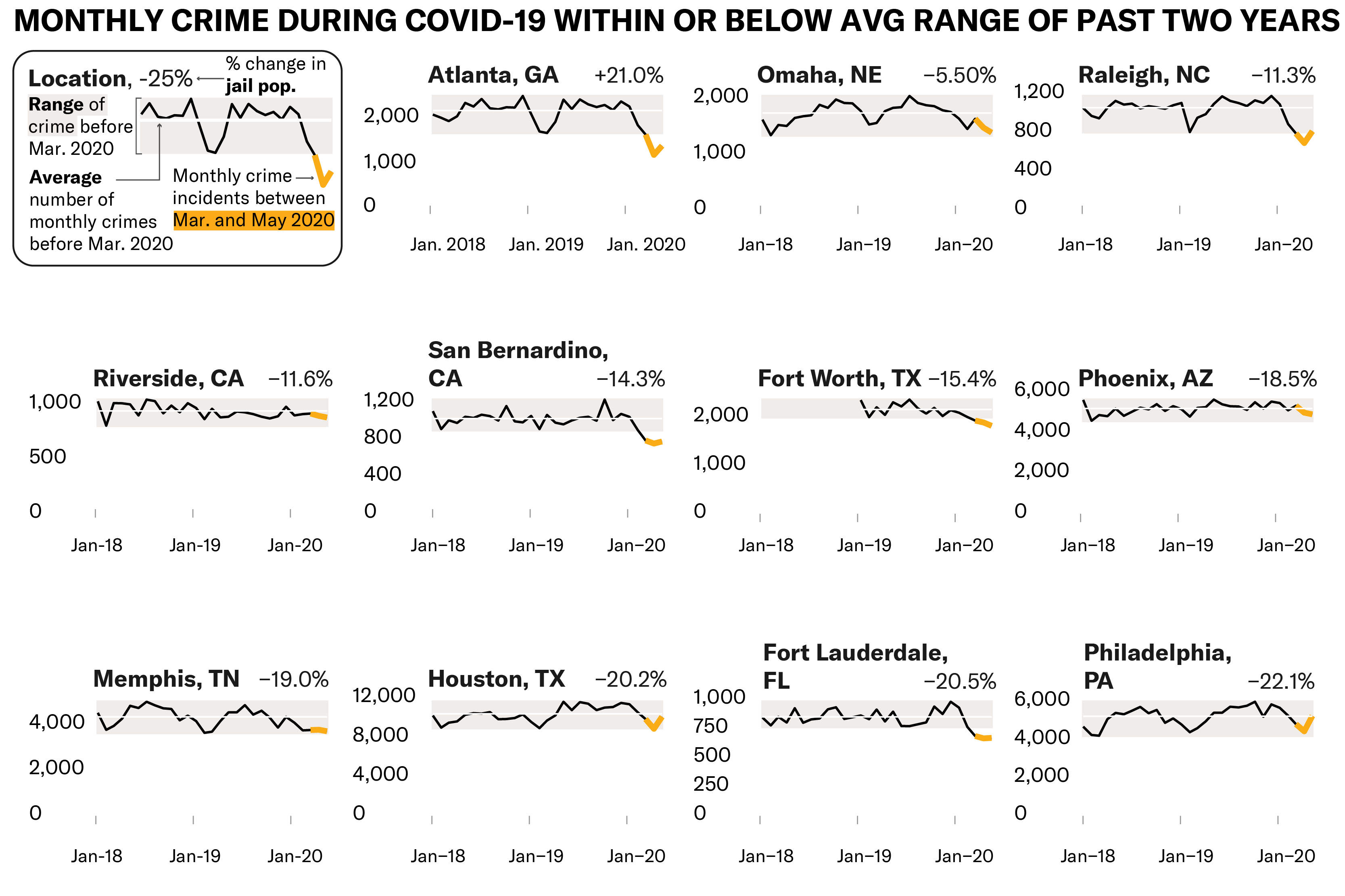

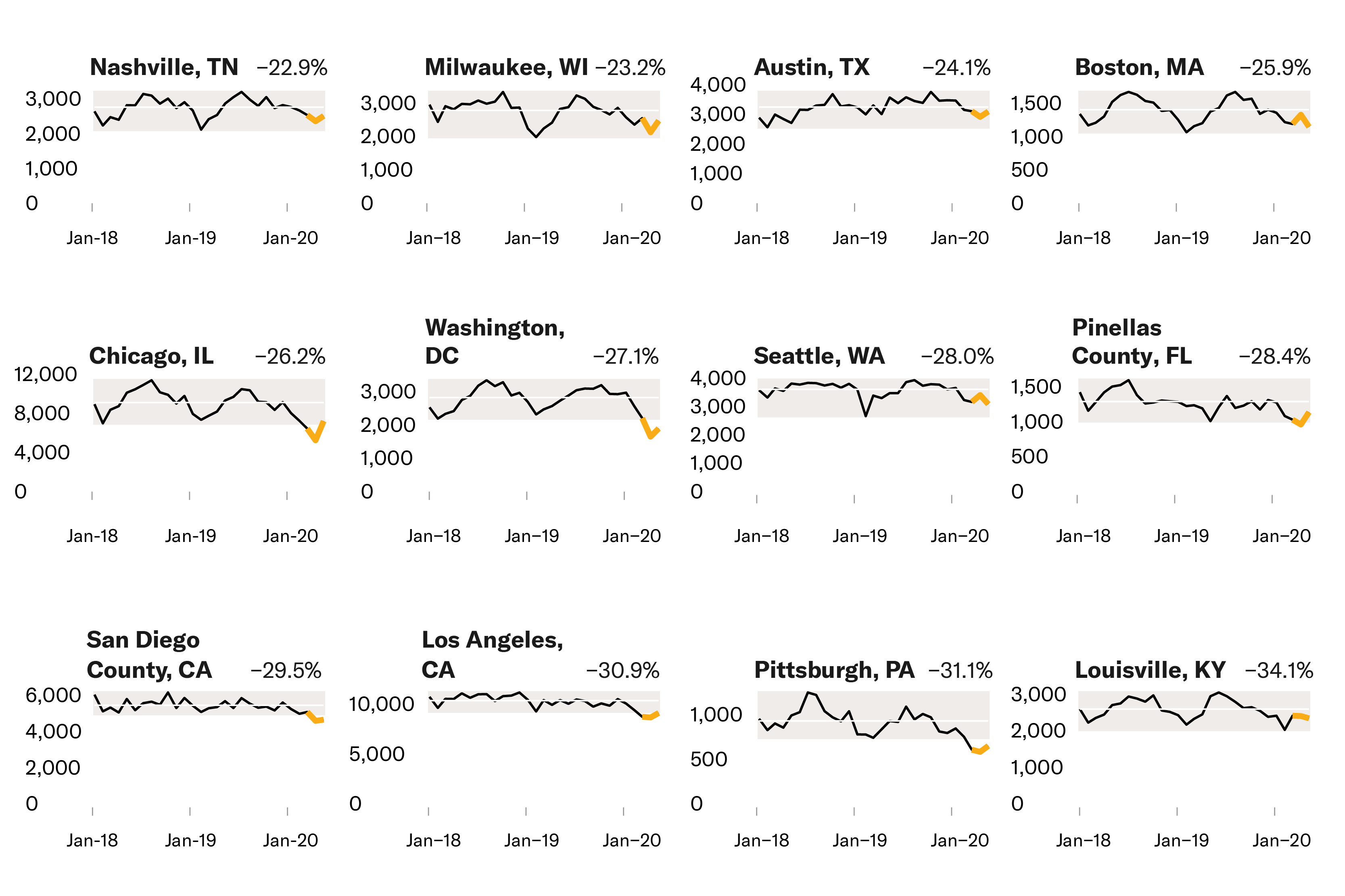

We found no evidence of any spikes in crime in any of the 29 locations, even when comparing monthly trends over the past two years. The release of incarcerated people from jails has saved lives both in jails and in the community, all while monthly crime trends were within or below average ranges in every city.

The team’s findings were in line with recent reports that documented certain types of crime have gone down during the COVID-19 pandemic, which many attribute to stay-at-home orders and decreased overall activity. City-level crime trends are complex and influenced by many factors, including temperature, with crime rates typically rising in the summer months. The analysis confirmed that the amount by which a county changed its jail population wasn’t correlated with the amount of change in crime.

This confirmation comes at a time when reducing jail populations is urgently necessary. The epidemiological model the ACLU developed in partnership with academics in April illustrated the profound risk COVID-19 presents to people in carceral facilities and their surrounding communities. The model found that swift action to reduce jail populations could save lives, but inaction could lead to an estimated 100,000 deaths in jails and the surrounding communities. Since then, COVID-19 has continued to spread rampantly through jails, prisons, and immigration detention centers — more than 50,000 people in prison have tested positive for the coronavirus, and over 600 have died. Further research has confirmed what we feared: Cycling through a jail is one of the largest risk factors for COVID-19 transmission. For Black and Brown people already disproportionately harmed by the criminal justice system, this system only exacerbates COVID-19’s unequal impact.

Arresting fewer people and releasing people from jail during a pandemic, as the 29 localities highlighted here have done, has undoubtedly saved lives in jails and in surrounding communities. What’s more, crime was lower this spring in nearly every location, and the amount of decarceration or incarceration appears uncorrelated with crime patterns. No state has gone far enough, and all should continue to reduce their jail, prison, and detention center populations, particularly for those who are most vulnerable. The potentially fatal threat of COVID-19 in jails and prisons, and the risk of transmission between jail staff and the surrounding populations, should be reason enough to release as many people as possible.

As states struggle to return to “normal,” many life-saving policies are being quietly ended. California rescinded a statewide policy setting bail to $0 for low-level offenses, even as Los Angeles County continues to see record levels of new coronavirus cases. The threat of COVID-19 is still very much alive, and it highlights the arbitrary nature of our criminal legal system. Any and all policies to reduce arrests in light of COVID-19 should extend indefinitely, and should not be replaced with a system of fines and fees.

The data shows: We don’t have to choose between public safety and public health. Reducing jail populations saves lives, and these reductions must continue.

METHODOLOGY

- We found crime data individually for each city or county. A spreadsheet tracking the datasets used for each location can be found here.

- Because each location’s crime dataset was drawn from separate sources and contained varying categorizations of crime, crime patterns should not be compared between cities. Additionally, because police data is often dynamic and constantly updated based on new reports, incidents may have changed since the time of analysis (early July, 2020).

- We analyzed only “Part 1” crimes (as defined by UCR) because they represent the offenses most likely to be consistently reported to the police. This classification was often manual, so should be viewed as estimates. Our code to clean and analyze the data can be found here. Some cities report crime data at the offense level, which sometimes includes multiple rows of charges per incident; others report at the incident level, only identifying the individual’s highest offense, and other cities report their data already aggregated at the monthly incident level. For each location with daily data, we aggregated the number of incidents to the month level, using each set of data’s unique identifier to mark one incident of crime. For data with many missing or null unique identifiers, we created a unique identifier based on time, date, and location where possible to reasonably estimate.

- When calculating the percent change in crimes between 2020 and 2019, we used the average number of crimes between March and May for both years. One exception was Portland, OR, where data was only available through April 2020. We calculated the percent change using just March and April data for both years.

- We primarily used the Vera Institute’s tracking of jail populations during COVID-19 to calculate incarceration/decarceration rates. We used the dates of 2/29/20 and 4/30/20 to look at change in jail populations. When jail population data on 2/29/20 and 4/30/20 was not available through Vera’s tracking or other public collection efforts, we obtained jail population numbers from local news reports. Date ranges of the “decarceration” time periods in these localities and accompanying alternative data sources are available here.