At the end of the year many news sources review a year’s worth of obituaries, usually the passing of the famous. Neil Armstrong and Sally Ride. Whitney Houston, Dave Brubeck. Joe Paterno, a reminder that people’s lives are complicated, and we don’t really know public people as we think we do. Rodney King. Sherman Helmsley. Tony Scott and Don Cornelius, powerful men in entertainment. Etta James, Donna Summer, and Levon Helm.

Less remarked are the people we killed: those executed under the laws of some of these United States. Except for the families of the executed and the survivors of the murdered, few of us really know much about the condemned: maybe a paragraph about the crime and the meal they chose as their last. (Except in Texas, where they no longer provide a last meal to those who are about to die).

There were 43 executions in the United States in 2012. The third was Edwin Hart Turner, executed despite severe mental illness by the State of Mississippi on Feb. 3rd.

Georgia and Ohio both spared condemned men with disabling mental disorders, but Texas did not, executing Yokamon Hearn, despite the fact that his lawyer at trial had not seen fit to tell the sentencing jury about his “clear and consistent evidence of brain damage,” evident to all since he was a young child. The criminal justice “system” not only failed to give him a trial lawyer, but his appeal and his habeas were botched too, and there is no evidence that the Board of Pardons or the governor gave his case a passing glance. Certainly not a vote of mercy, despite pleas from the United Nations.

Andy Griffith died in 2012. An actor with much work, none of it better known than his embodiment of the kindly and thoughtful sheriff of the fictional Mayberry. Robert Moorman, executed by Arizona this year, did not grow up in Mayberry. Moorman was born to a 15-year-old prostitute who drank heavily, which may have contributed to his mental retardation and her death, two years later. After his alcoholic grandfather gave him up, Bobby Moorman was placed in foster care with a sexual abuser. He was 13 the first time he was institutionalized for mental illness.

Oklahoma killed Garry Allen on the day the country re-elected President Obama, Nov. 6. Allen’s execution had been stayed many times on the grounds of his unquestioned mental illness. His final words were spoken in a slurred voice, and consisted of rambling incoherent comments about the election. He appeared startled when told that the execution was about to begin. Oklahoma executed 6 people this year, but the Pardon Board would have spared Allen. Not the governor though.

That’s the 2012 track record of the Big Four: Mississippi, Arizona, Oklahoma and Texas. These four states are responsible for more than three-quarters of those executed. Only nine states in total carried out executions in 2013. One of the nine, Delaware, only appears in the roster because it executed one of the two “volunteers,” meaning men who gave up their right to appeal and committed suicide by state. The other 41 executed spent many decades on death row, a suffering that in itself has been found unacceptable in other countries.

The other death penalty news of 2012: executions are down, death sentences are down, and many people in the United States who once supported the death penalty are now convinced that it is too expensive, too fraught with error, and can never be free from race and class discrimination. Some have come to hope that the U.S. will join the majority of nations who see capital punishment as a human rights violation.

So perhaps the last thought of the year should be for those who did not get executed. While those of us who are dedicated to ending the death penalty will not forget the executed nor the victims’ families, we find hope in the names of those re-sentenced to life, or freed. In 2012, Marcus Robinson, Timon Golphin, Christina Walters, and Quintel Augustine, four North Carolina Death Row inmates, were resentenced to life in prison under the Racial Justice Act. LaSamuel Gamble in Alabama and Ray McNeil in North Carolina were both resentenced to life after thorough litigation. And Damon Thibodeaux, an innocent man freed from Louisiana’s Death Row, is starting his first free year.

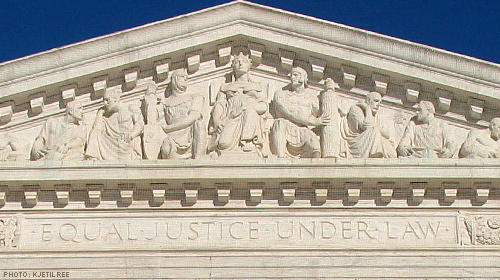

These are seven names of seven living people – successful cases from the ACLU Capital Punishment Project’s year. All over the country, quietly and notoriously, other condemned persons have been freed, or resentenced to life in prison. We will end the death penalty in the United States by lobbying in the states to abolish; by seeking help from international law and partners; by litigating big systemic issues in the Supreme Court; by working with victims’ families and other allies to increase public opposition.

And we will bring an end to capital punishment this way. One life at a time.

Learn more about the death penalty: Sign up for breaking news alerts, follow us on Twitter, and like us on Facebook.