One Key Reform Can Fight Voter Suppression

This was originally published on Democracy Docket.

There’s one trend election observers can be confident of year after year: Record turnout will always be swiftly followed by a tidal wave of voter suppression efforts.

The 2008 election was the first presidential election in American history in which voters of color constituted one quarter of the nation’s eligible electorate. That election also saw a massive shift in the racial composition of early in-person voting, with Black voters casting their votes early in person more frequently than white voters (an estimated 24 percent to 17 percent nationally). This record turnout was followed by an unprecedented effort to cut back early in-person voting in states including North Carolina, Ohio, Wisconsin and Florida — which notoriously tried to ban voting on Sundays, a move that would have effectively eliminated Souls to the Polls efforts by Black churches.

We are now witnessing a rerun. The 2020 presidential election saw more than 159 million votes cast — shattering the record for the most voters to ever participate in an election in American history by more than 20 million voters. The 2020 election had the highest turnout rate since the 1900 presidential election. Seven of the 10 states where turnout rose the most conducted their elections entirely or mostly by mail. The percentage of Black voters casting their ballots by mail more than doubled from about 18 percent of Black voters in 2016, to an estimated 38 percent in 2020.

And like clockwork, we are now seeing an onslaught of proposed legislation to cut back voting by mail, including in states like Arizona, Iowa, Florida, Wisconsin — and most notoriously, Georgia. In Georgia, pending legislation would require voters to submit photocopies of their identification twice when seeking to vote by mail; bar elections officials from affirmatively mailing absentee ballot applications to voters; reduce the window for requesting absentee ballots; place restrictions on drop boxes for returning ballots; and eliminate no-excuse absentee voting altogether.

It’s not just absentee balloting that’s under attack — invoking the Big Lie, legislators throughout the country have proposed not only a staggering array of other restrictions on registration and voting, but even restrictions on citizen-led ballot initiatives and bans on donations for elections administration resources like PPE.

What can be done?

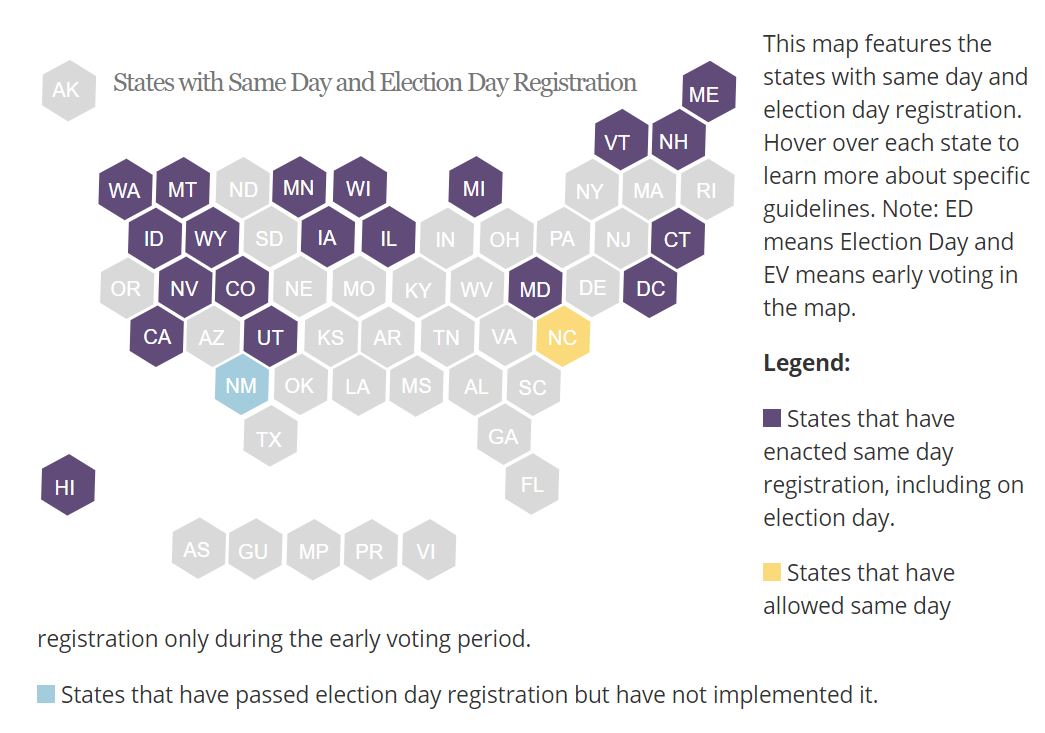

The single reform that would do the most to fight back against the voter suppression efforts sweeping the country is Election Day Registration (EDR), which allows eligible voters to register to vote and cast a ballot at the same time on Election Day, effectively eliminating earlier registration deadlines. The 10 states with the highest turnout in 2020 all had same-day registration, with nine of the top 10 offering same-day registration on Election Day (one of the top 10, North Carolina, only offers same-day registration during its early voting period). The consensus among political scientists is that EDR boosts turnout by two to 10 percentage points, with particularly strong gains among historically lower-turnout or disenfranchised groups like young, lower-income, and Black voters.

Allowing registration and voting on the same day reduces the logistical hurdles associated with voting by simplifying a two-step process into a single trip to a polling location. EDR also allows voters to update or correct their registrations on Election Day, which prevents the disenfranchisement of those who have recently moved or who have been erroneously purged from the rolls. And perhaps most significantly, voter interest is at its highest once voting has commenced; EDR capitalizes on that interest to bring new voters into the process.

The good news is that 21 states and the District of Columbia have already enacted some form of same-day registration, as set forth on this map from the National Conference of State Legislatures:

These states are a mix of “blue” states (for example, California, Colorado); “red” states (Idaho, Utah, Wyoming); and “purple” states (Maine and Wisconsin). EDR is not just popular across the ideological spectrum, it is increasingly so, as six states have adopted it since the beginning of 2018: Maryland, Michigan, Nevada, New Mexico, Utah, and Washington.

Efforts to expand EDR should focus on states that currently lack it and where the political environment would seem to make it a no-brainer, such as Massachusetts and New York which are both currently considering EDR. Let’s hope they find the political will, because the absence of EDR in these two states is a common talking point by opponents of expanding voting rights in other states.

We also need to fight back against an effort this year to eliminate EDR in Montana; if successful, it would make Montana the first state in the country to repeal EDR. And ultimately, national legislation for EDR, as is contained in H.R. 1 — which passed the House in early March — would establish a national standard so that all Americans can share in the same registration and voting opportunities enjoyed by people in states like Utah and Wyoming.

But there’s an important caveat. While EDR and other reforms aimed at increasing voter turnout are absolutely essential to fighting back against voter suppression, they are insufficient to cure all that ails our democracy today. The very structures of our political system are conspiring to prevent the will of the majority from translating into representative self-government.

For one thing, extreme gerrymandering has largely locked up the political process in many states, distorting elections results. After the 2017 and 2018 elections, five state legislatures were controlled by parties that had lost a majority of the statewide vote (Virginia, Wisconsin, Pennsylvania, Michigan, and North Carolina). The next round of redistricting, which starts later this year, presents opportunities to address these distortions. But failure to reform these maps could entrench another decade of minority rule in these and other states.

At the national level, the anti-majoritarian problems facing our democracy are likely to grow even worse. People of color already constitute a majority of children in the U.S., and are projected by 2045 to be a majority of the total U.S. population. But at roughly the same time, about 70 percent of the population will live in just 15 states — which means that just 30 percent of the country will choose 70 percent of Senators and a super-majority of the Electoral College. To compound matters, Americans across the ideological spectrum are increasingly falling prey to disinformation, finding difficulty agreeing on basic facts, and losing confidence in democracy itself.

Ultimately, we need to make registration and voting simpler and easier, and to boost turnout to respectable levels. But doing so will not solve everything. We need a renewed commitment to democracy itself, and to the basic principle that every individual should count equally in our political processes. That will be the work not of lawyers, but of all of us as Americans.