This case challenges Ohio’s practice of ‘purging’ or removing people who vote infrequently from its voting rolls. Since this practice began in 1994, hundreds of thousands have been eliminated from voter registration lists. Under Ohio’s rules, registered voters who do not participate in an election in a two-year period are sent a postcard from the Ohio Secretary of State’s office requesting a confirmation of address. If the voter does not respond to the notice or vote within the next two consecutive federal elections, i.e. four years, they are removed from the rolls without further notice.

Voting in the United States is not a ‘use it or lose it’ right. Ohio’s purge practice violates the 1993 National Voter Registration Act (NVRA) which explicitly prohibits removing voters solely because they did not vote in an election.

In April 2016, a suit was filed in Southern District of Ohio challenging Ohio’s purge process as a violation of the NVRA. The federal district court ruled for the plaintiffs in June 2016 and entered a preliminary injunction, which applied only to the November 2016 election. In September 2016, the Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit upheld the district court’s preliminary injunction – a move that allowed more than 7,500 voters who would have been purged to vote by provisional ballot in the presidential election. (This number does not account for all voters who were purged in the Supplemental Process.)

In February, Secretary of State Jon Husted sought Supreme Court review of the appellate court decision. The Supreme Court will hear oral arguments on this case on Nov. 8.

What is the legal principle at stake?

The right to vote includes the right to decide whether, when, and how to exercise that right. The National Voter Registration Act protects the right to vote, and aims to increase the number of registered voters and to ensure that states properly maintain their voter rolls. It allows states to remove voters from rolls only for reasons listed in the law -- such as by request of the voter or in the case of death. It specifically prohibits states from removing voters for failure to vote.

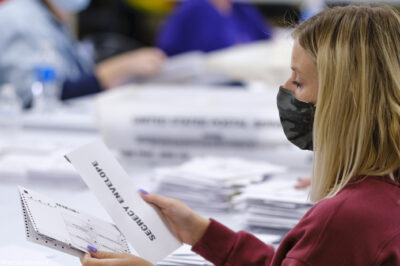

Mr. Husted’s office has directed county boards of elections to remove infrequent voters from their rolls through a practice called the Supplemental Process. This process wrongly assumes that voters who have not cast a ballot in a two-year period have changed addresses. Those voters are then sent a notice in the mail requesting a confirmation of address, and, if they do not respond and do not vote in the next four years, their names are removed from the registration rolls.

Many Americans only vote in presidential elections, every four years. As a result, voters in Ohio can get caught up in the state’s purge practice time and time again – finding themselves under constant threat of being removed from the rolls.

How many people were affected in Ohio’s voter purge?

In 2015, hundreds of thousands of Ohioans who had not voted since 2008 were purged through the Supplemental Process, with over 40,000 removed in Cuyahoga County alone. Many went to the polls in November 2015 and March 2016 only to learn that their names no longer appeared on the lists and were barred from casting a ballot. Ohio’s process disproportionately impacts low-income voters and voters of color.

Who are the plaintiffs?

The individual plaintiff is Larry Harmon, a 59-year-old Navy veteran who was purged by the Supplemental Process. He had been voting since 1976 and had lived in the same home for more than a decade. Mr. Harmon voted in 2008 presidential election but chose not to vote in the 2010 midterm elections, the 2012 presidential election, and the 2014 midterm elections. In November 2015, he went to his polling place to vote in the primary election, and learned for the first time that he had been removed from the rolls.

Mr. Harmon and two organizations that work to register voters – the A. Philip Randolph Institute (APRI), an organization for African-American trade unionists and the Northeast Ohio Coalition for the Homeless – are represented in this lawsuit by the ACLU, the ACLU of Ohio, and Demos, a public policy organization.

What are the implications of this case?

The federal law governs the registration list maintenance practices of all but six of the 50 states. The six states that are exempt are North Dakota, Idaho, Minnesota, New Hampshire, Wisconsin, and Wyoming. North Dakota is exempt for having continuously allowed its residents to vote in federal elections without registering, while Idaho, Minnesota, New Hampshire, Wisconsin, and Wyoming have continuously offered Election Day voter registration for federal general elections.

It is critically important that the Supreme Court strike down Ohio’s illegal process and make it clear to all states that efforts to deny eligible voters their constitutional right to vote will not be condoned.