Terrifying is not a word I’d use to describe myself. I don’t even think it’s a word most other people would use to describe me. But I guess it all depends on your perspective.

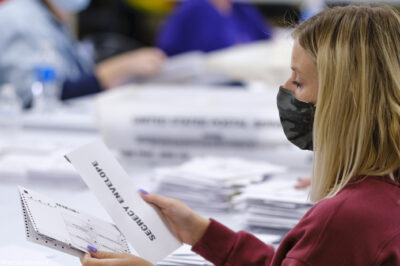

I was in East Tampa, Florida a few weeks before the primary, to assess the state’s new election laws, which add prohibitively onerous requirements to anyone who wants to register voters there. I was looking for people who register voters, and the people they sign up, to try to understand how the legislation will affect things on the ground.

East Tampa was a good place to start, because people are still registering voters there: it’s one of a number of jurisdictions where the Voting Rights Act of 1965 requires the federal government to approve any changes to election laws.

It was Monday morning, Martin Luther King Day. The community was getting ready for its annual parade. And Yvette — an African American woman who has registered hundreds of voters in the last couple of years — was planning a voter registration drive in a high school parking lot near the end of the parade route.

When I got to the school, Yvette wasn’t there yet. But a group of black sorority sisters, who were also planning to register voters, were. I introduced myself to one, and asked a few vague questions about their plans. I didn’t get many answers. But I didn’t think much of it.

Until I got the call from Yvette.

She had arrived while I was out with a camera crew, shooting street scenes around the parade route.

She asked me where I was, then barely waited for my answer before she said: “You scared them. You scared them so bad!”

I was perplexed. Who had I scared?

The sorority sisters.

“I got out of the car,” Yvette went on, “and they came running over and said ‘there’s a white lady who was looking for you. Asking about us registering voters.” “I had to tell them ‘she’s alright. She’s with me. She’s alright.”

I felt terrible. But I was also confused. I hadn’t tried to interview them on tape or on camera. I didn’t even have a notebook. The questions I’d asked were hardly probing. And come on, I work for the ACLU. As for the white part, well, it’s true. And according to Yvette, anyway, that was the problem.

“That’s what white folks have done to black people down here.”

I hadn’t felt that there before. The day before, I’d been warmly welcomed in an African-American church. And I’d walked around the Black Heritage Festival downtown for several hours, talking to people. But at church, I’d been introduced by the pastor. And at the Festival, I’d been with Yvette and her friend, another African-American woman. Maybe with somebody vouching for me, people were just too polite to tell me I was scary.

Race did come up a lot that weekend, and not just in the context of registering voters. The local cameraman I hired — who is white — called me the night before the shoot, to ask if it was safe to bring his equipment to the parade. He prefaced the question with the caveat that he didn’t want to sound racist — and followed it with a story of his mother getting caught up in race riots.

Jay-walking across an empty downtown street with Yvette, she teased her friend that they could get arrested for that kind of behavior. Her friend’s answer? “Well, maybe not with the white lady here.”

That there’s deeply ingrained mistrust on both sides is hardly news. But it’s disturbing for a whole host of reasons, not least because of its implications for voter registration.

Making it hard for third parties to register voters may not sound like a big deal. But the data shows African-Americans and Latinos are far more likely than whites to register through voter registration drives, which are often hosted by third parties like the League of Women Voters or the NAACP. (The new rules are so tough that the League of Women Voters has stopped working in Florida.) As Yvette and her friends told me repeatedly, no white person — no matter how well-meaning — will convince an African-American in East Tampa to register to vote.

Not counting my camera crew or police officers, the only white people I saw in East Tampa that day were two representatives of the county elections office and three Obama supporters.

Learn more about voting rights: Sign up for breaking news alerts, follow us on Twitter, and like us on Facebook.