Family Surveillance by Algorithm: The Rapidly Spreading Tools Few Have Heard Of

Last month, police took American Idol finalist Syesha Mercado’s days-old newborn Ast away because she had not reported her daughter’s birth to authorities, while she was still fighting to regain custody of her son from the state. In February 2021, Syesha had taken her 13-month-old son Amen’Ra to a hospital because he had difficulty transitioning from breast milk to formula and was refusing to eat. What should have been an ordinary medical visit for a new mom prompted a state-contracted child abuse pediatrician with a known history of wrongfully reporting medical conditions as child abuse to call child welfare. Authorities took custody of Amen’Ra on the grounds that Syesha had neglected him. Syesha has been reunited with Ast after substantial media attention and public outrage, but continues to fight for the return of Amen’Ra.

Meanwhile, it took over a year and a half for Erin Yellow Robe, a member of the Crow Creek Sioux Tribe, to be reunited with her children. Based on an unsubstantiated rumor that Erin was misusing prescription pills, authorities took custody of her children and placed them with white foster parents — despite the federal Indian Child Welfare Act’s requirements and the willingness of relatives and tribal members to care for the children.

For white families, these scenarios typically do not lead to child welfare involvement. For Black and Indigenous families, they often lead to years — potentially a lifetime — of ensnarement in the child welfare system or, as some are now more appropriately calling it, the family regulation system.

Child Welfare as Disparate Policing

Our country’s latest reckoning with structural racism has involved critical reflection on the role of the criminal justice system, education policy, and housing practices in perpetuating racial inequity. The family regulation system needs to be added to this list, along with the algorithms working behind the scenes. That’s why the ACLU has conducted a nationwide survey to learn more about these tools.

Women and children who are Indigenous, Black, or experiencing poverty are disproportionately placed under child welfare’s scrutiny. Once there, Indigenous and Black families fare worse than their white counterparts at nearly every critical step. These disparities are partly the legacy of past social practices and government policies that sought to tear apart Indigenous and Black families. But the disparities are also the result of the continued policing of women in recent years through child welfare practices, public benefits laws, the failed war on drugs, and other criminal justice policies that punish women who fail to conform to particular conceptions of “fit mothers.”

Turning to Predictive Analytics for Solutions

Many child welfare agencies have begun turning to risk assessment tools for reasons ranging from wanting the ability to predict which children are at higher risk for maltreatment to improving agency operations. Allegheny County, Pennsylvania has been using the Allegheny Family Screening Tool (AFST) since 2016. The AFST generates a risk score for complaints received through the county’s child maltreatment hotline by looking at whether certain characteristics of the agency’s past cases are also present in the complaint allegations. Key among these characteristics are family member demographics and prior involvement with the county’s child welfare, jail, juvenile probation, and behavioral health systems. Intake staff then use this risk score as an aide in deciding whether or not to follow up on a complaint with a home study or a formal investigation, or to dismiss it outright.

Like their criminal justice analogues, however, child welfare risk assessment tools do not predict the future. For instance, a recidivism risk assessment tool measures the odds that a person will be arrested in the future, not the odds that they will actually commit a crime. Just as being under arrest doesn’t necessarily mean you did something illegal, a child’s removal from the home, often the target of a prediction model, doesn’t necessarily mean a child was in fact maltreated.

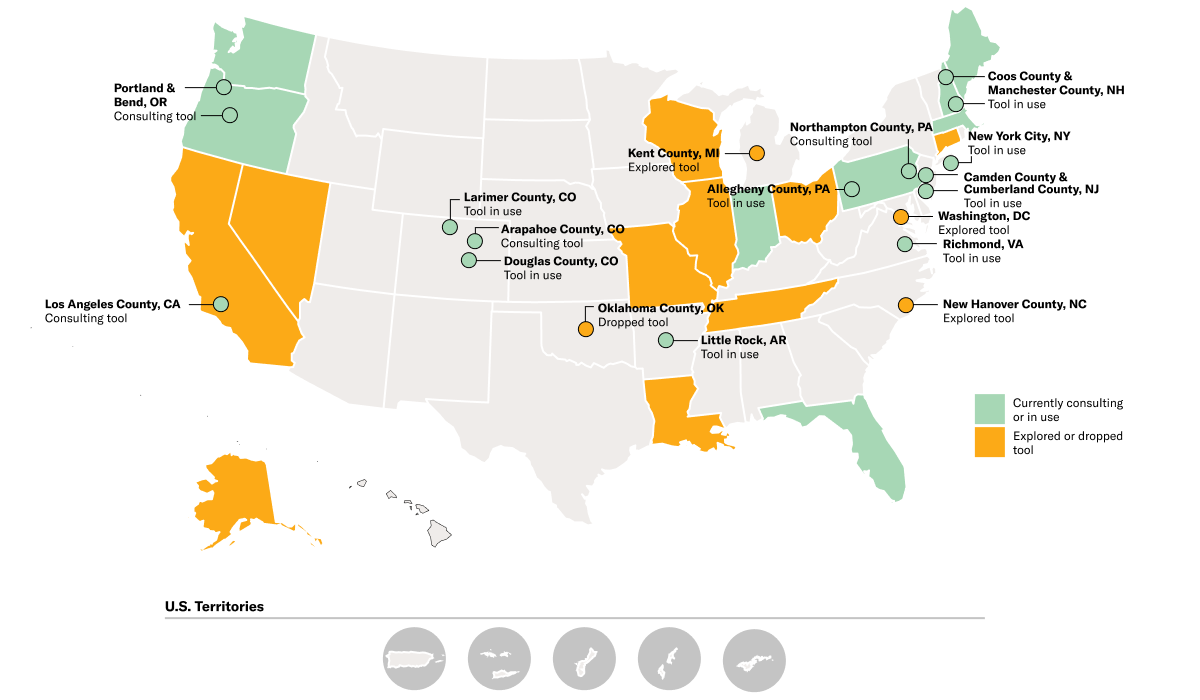

We examined how many jurisdictions across the 50 states, D.C., and U.S. territories are using one category of predictive analytics tools: models that systematically use data collected by jurisdictions’ public agencies to attempt to predict the likelihood that a child in a given situation or location will be maltreated. Here’s what we found:

- Local or state child welfare agencies in at least 26 states plus D.C. have considered using such predictive tools. Of these, jurisdictions in at least 11 states are currently using them.

- Large jurisdictions like New York City, Oregon, and Allegheny County have been using predictive analytics for several years now.

- Some tools currently in use, such as the AFST, are used when deciding whether to refer a complaint for further agency action, while others are used to flag open cases for closer review because the tool deems them to be higher-risk scenarios.

The Flaws of Predictive Analytics

Despite the growing popularity of these tools, few families or advocates have heard about them, much less provided meaningful input into their development and use. Yet countless policy choices and value judgments are made in the course of creating and using the tool, any or all of which can impact whether the tool promotes “fairness” or reduces racial disproportionality in agency action.

Moreover, like the tools we have seen in the criminal legal system, any tool built from a jurisdiction’s historical data runs the risk of continuing and increasing existing bias. Historically over-regulated and over-separated communities may get caught in a feedback loop that quickly magnifies the biases in these systems. Who decides what “high risk” means? When a caseworker sees a “high” risk score for a Black person, do they respond in the same way as they would for a white person?

Ultimately, we must ask whether these tools are the best way to spend hundreds of thousands, if not millions of dollars, when such funds are urgently needed to help families avoid the crises that lead to abuse and neglect allegations.

What the ACLU is Doing

It’s critical that we interrogate these tools before they become entrenched, as they have in the criminal justice system. Information about the data used to create a predictive algorithm, the policy choices embedded in the tool, and the tool’s impact both system-wide and in individual cases are some of the things that should be disclosed to the public before a tool is adopted and throughout its use. In addition to such transparency, jurisdictions need to make available opportunities to question and contest a tool’s implementation or application in a specific instance if our policymakers and elected officials are to be held accountable for the rules and penalties enforced through such tools.

In this vein, the ACLU has requested data from Allegheny County and other jurisdictions to independently evaluate the design and impact of their predictive analytics tools and any measures they may be taking to address fairness, due process, and civil liberty concerns.

It’s time that all of us ask our local policymakers to end the unnecessary and harmful policing of families through the family regulation system.

Read the full white paper:

Family Surveillance by Algorithm

By Anjana Samant, Aaron Horowitz, Kath Xu, and Sophie BeiersOur country’s latest reckoning with structural racism has involved critical reflection on the role of the criminal justice system, education policy, and housing practices in perpetuating racial inequity. But another area long overdue for collective reexamination is the child welfare system and the algorithms working

Source: American Civil Liberties Union