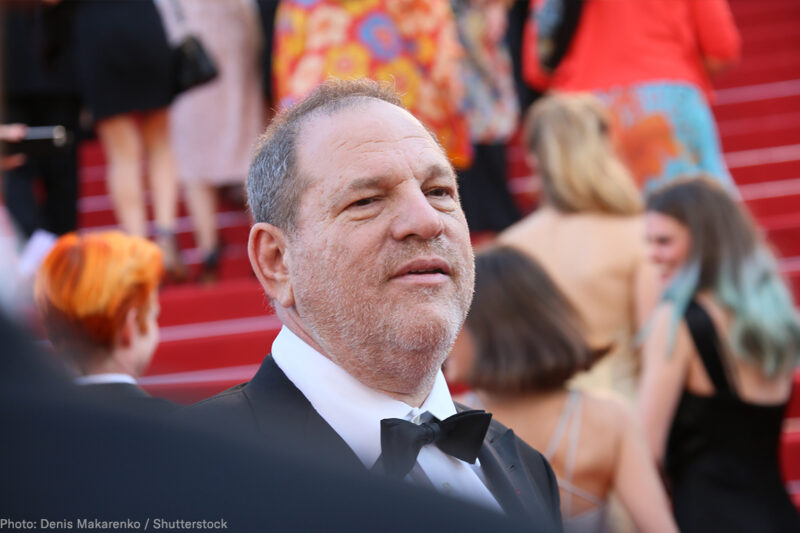

In the wake of bombshell reports by the The New York Times and The New Yorker detailing three decades of sexual misconduct by movie mogul Harvey Weinstein, the revelations keep coming. So do the questions: How did such flagrant misconduct stay an “open secret” for so long? Just how many women were harmed? And how do we make sure that such an egregious abuse of power never happens again?

Sexual harassment that is “severe or pervasive” was deemed by the Supreme Court to be illegal sex discrimination more than 30 years ago, when Mechelle Vinson, a bank employee in Washington, D.C., challenged her manager’s three-year campaign of abuse, including rape. And it’s been nearly a quarter-century since the court clarified that conduct becomes illegal harassment at the point that a “reasonable person” would find it abusive, even if it never gets physical.

So it shouldn’t be news to anyone that arriving at a business meeting in a bathrobe and asking for a massage crosses the line. Yet here we are again. Fox News, Uber, the Marine Corps — each new sexual harassment scandal prompts an outpouring of “me, too” stories to remind us that, whatever the law might say about such conduct, culture follows different rules.

As these and other scandals show, that culture can be toxic in fields where women are in the minority, especially in leadership roles: entertainment, media, and the military, not to mention Wall Street, law enforcement, and science, technology, engineering, and math (STEM) fields. Indeed, Weinstein was enabled by an industry in which the top executives at film studios, according to a 2016 study, are on average 80 percent male — resulting in rampant discrimination in behind-the-camera hiring decisions, as the ACLU has successfully argued to the U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission.

It’s time to get to work on making antidiscrimination law’s promise a reality. Here’s how.

Know the warning signs and be vigilant. Last year, the EEOC Select Task Force on the Study of Harassment in the Workplace issued a landmark report identifying 12 “risk factors for harassment.” Among them are “workplaces with ‘high value’ employees” — stars who receive hands-off treatment when it comes to workplace rules — along with “homogeneous workforces” and “workplaces with significant power disparities.” Sound familiar? (Needless to say, if it is true, as reported, that Weinstein’s employment contract contemplated the Weinstein Company making payouts to victims, the company wasn’t just risking, but assuming, that abuse would occur.) Employers are wise to remain vigilant to worrying trends — like why are the rates of women’s turnover so high? — and to not shrink from answering such questions.

Set the tone from the top — and show you mean it. Most businesses today claim “zero tolerance” for harassment, and some may even have an anti-harassment policy. But these are worthless without accountability. Indeed, companies that have managed to build businesses worth billions are curiously helpless when it comes to tackling harassment. Often, they wait for scandal to strike, then conduct an aggressive investigation and take decisive action against wrongdoers. For example, Fox hired a prestigious law firm, as the Weinstein Company just did; Uber hired former Attorney General Eric Holder. Instead, company leaders should state their intolerance of harassment loudly, often, and through multiple channels — and when they are put on notice of a problem, must act promptly and decisively.

Men: Be allies in deed, not just word. More than 80 percent of sexual harassment charges filed with the EEOC are brought by women. Put bluntly, nothing will change if they are the only ones monitoring our work environments. Along with vocal male leadership, it’s also critical that every male ally in the rank and file be, in the words of a recent Harvard Business Review report, “an intentional exemplar and fierce watchdog for the behavior of other men.”

Make it safe to come forward. Study after study tells us what we already know: Fear of retaliation or other adverse action keeps victims silent. Indeed, one report found roughly 90 percent of people who say they have been harassed never filed a formal complaint. No wonder harassment scandals follow a predictable arc. A woman or two speak up, then another, and another, until the tally is in the double digits. Employers must not let those numbers multiply in silence. Rather they must make plain, through words and actions, that each person who speaks up is safe.

As history has shown, dislodging the cultural roots of sexual harassment will take years, even generations. It is possible, but we mustn’t wait until the next big scandal to relearn what women have been telling us for decades: Harassment happens in virtually every workplace. Employers need to deal with it. Now.