ACLU Releases Cell Phone Tracking Documents From Some 200 Police Departments Nationwide

Results Show Pervasive and Frequent Violations of Americans’ Privacy Rights

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE

CONTACT: (212) 549-2666; media@aclu.org

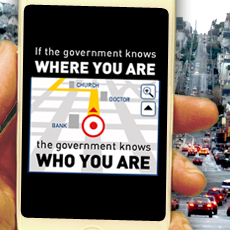

NEW YORK – Many of the approximately 200 law enforcement agencies responding to public record requests by the American Civil Liberties Union track cell phones without a warrant, according to documents newly released by the ACLU.

A small number of agencies, such as in North Las Vegas and Wichita, said they do obtain warrants based on probable cause before tracking. Others, such as the Kentucky State Police, said they use varying legal standards, such as a warrant or a less-strict subpoena. The result is unclear or inconsistent legal standards from town to town that frequently fall short of probable cause.

“What we have learned is disturbing. The government should have to get a warrant before tracking cell phones. That is what is necessary to protect Americans’ privacy, and it is also what is required under the Constitution,” said Catherine Crump, staff attorney for the ACLU Speech, Privacy and Technology Project. “The fact that some law enforcement agencies do get warrants shows that a probable cause requirement is a completely reasonable and workable policy, allowing police to protect both public safety and privacy.”

Last August, in an unprecedented effort to penetrate the secrecy around the policies, 35 ACLU affiliates around the country filed over 380 requests under states' freedom of information laws. The ACLU asked state and local law enforcement agencies about their policies, procedures and practices for tracking cell phones.

The responses varied widely, and many agencies did not respond at all. The documents included statements of policy, memos, police requests to cell phone companies (sometimes in the form of a subpoena or warrant), and invoices and manuals from cell phone companies explaining their procedures and prices for turning over location data.

The documents provide an eye-opening view of police surveillance of Americans. In Wilson County, N.C., police obtain cell phone tracking data where it is “relevant and material” to an ongoing investigation – a standard much lower than probable cause. Police in Lincoln, Neb., without demonstrating probable cause, obtain even GPS location data, which is more precise than cell tower location information. In Tucson, Ariz., police sometimes obtain cell phones numbers for all of the phones at a particular location at a certain time (this practice is known as a “tower dump”).

The ACLU supports bipartisan legislation currently pending in both the House of Representatives and the Senate that would address this problem called the Geolocation Privacy and Surveillance (GPS) Act. It would require law enforcement officers to obtain a warrant to access location information from cell phones or GPS devices. It would also mandate that private telecommunications companies obtain their customers’ consent before collecting location data. At least 11 state legislatures are also considering bills related to location tracking.

The U.S. Supreme Court in January held in U.S. v. Jones, that prolonged location tracking is a search under the Fourth Amendment, but the effects of that ruling on law enforcement have yet to be seen.

A detailed analysis of the documents is available at:

www.aclu.org/files/assets/cell_phone_tracking_documents_-_final.pdf

Links to the documents are available in an interactive map at:

www.aclu.org/maps/your-local-law-enforcement-tracking-your-cell-phones-l...

More information is available at:

www.aclu.org/locationtracking